Lab 4: probability distributions, averaging, and Jensen's inequality

© 2005 Ben Bolker

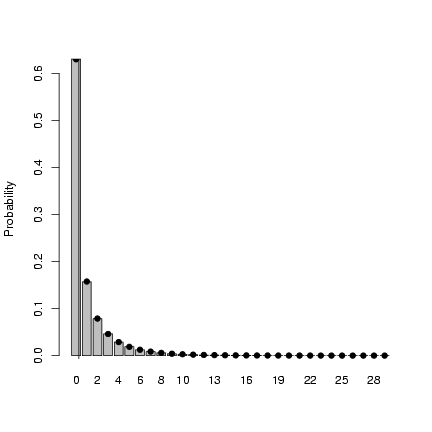

1 Random distributions in R

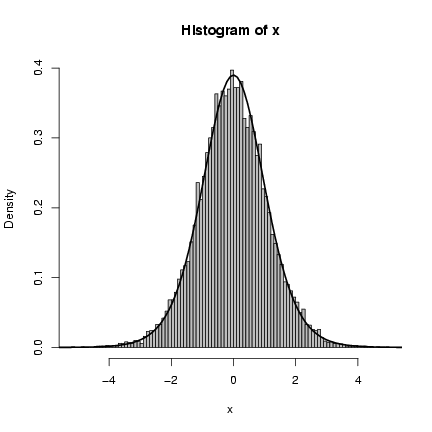

R knows about lots of probability distributions. For each, it

can generate random numbers drawn from the distribution

("deviates");

compute the cumulative distribution function and the probability

distribution

function; and compute the quantile function, which gives the

x value such that ò0x P(x) dx (area under the curve from 0

to x) is a specified value, such as 0.95 (think about "tail areas"

from standard statistics).

Figure 1: R functions for an arbitrary distribution

dist, showing density function (ddist),

cumulative distribution function (pdist),

quantile function (qdist), and

random-deviate function (rdist).

Let's take the binomial distribution (yet again) as an example.

Figure 1: R functions for an arbitrary distribution

dist, showing density function (ddist),

cumulative distribution function (pdist),

quantile function (qdist), and

random-deviate function (rdist).

Let's take the binomial distribution (yet again) as an example.

- rbinom(n,size,p) gives n random draws from the binomial

distribution with parameters size (total number of draws) and

p (probability of success on each draw).

You can give different parameters for each draw.

For example:

> rbinom(10, size = 8, p = 0.5)

[1] 3 6 3 4 6 7 4 3 2 2

> rbinom(3, size = 8, p = c(0.2, 0.4, 0.6))

[1] 2 4 7

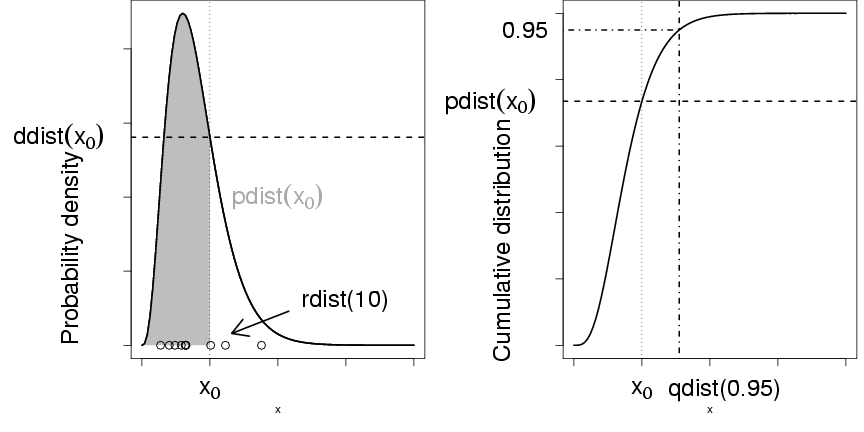

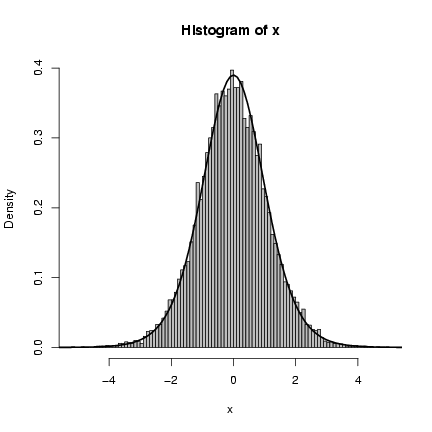

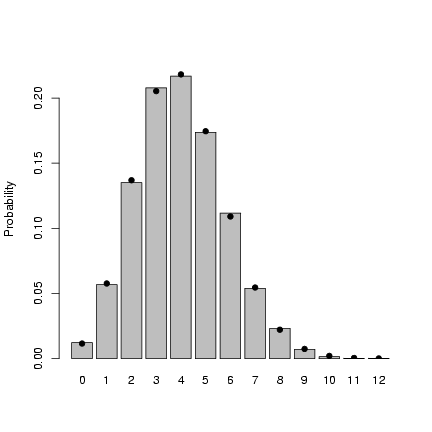

Figure 2 shows the result of drawing 200 values

from a binomial distribution with N=12 and p=0.1 and

plotting the results as a factor (with 200 draws

we don't have to worry about any of the 13 possible outcomes

getting missed and excluded from the plot):

> plot(factor(rbinom(200, size = 12, p = 0.1)), xlab = "# of successes",

+ ylab = "# of trials out of 200")

Figure 2: Results of rbinom

Figure 2: Results of rbinom

- dbinom(x,size,p) gives the value of the probability

distribution

function (pdf) at x (for a continous distribution,

the analogous function would compute the probability density

function). Since the binomial is discrete, x

has to be an integer, and the pdf is just the probability of getting

that many successes; if you try dbinom with a non-integer x, you'll get zero and a warning.

- pbinom(q,size,p) gives the value of the cumulative

distribution

function (cdf) at q (e.g. pbinom(7,size=10,prob=0.4));

- qbinom(p,size,prob) gives the quantile function,

where p is a number between 0 and 1 (an area under the pdf, or

value of the cdf) and qbinom is the value such that

P(X £ p)=q.

The quantile function Q is the inverse of the cumulative distribution

function C: if Q(p)=q then C(q)=p.

Example: qbinom(0.95,size=10,prob=0.4).

These four functions exist for each of the distributions R has built

in: e.g. for the normal distribution they're

rnorm(), pnorm(), dnorm(), qnorm().

Each distribution has its own set of parameters (so e.g. pnorm()

is pnorm(x,mean=0,sd=1)).

Exercise 1:

For the binomial distribution with 10 trials and a success probability

of 0.2:

- Pick 8 random values and sort them into increasing order

(if you set.seed(1001) beforehand, you should get X=0

(twice), X=2 (5 times), and X=4 and X=5 (once each)).

- Calculate the probabilities of getting 3, 4, or 5

successes. Answer:

[1] 0.20132659 0.08808038 0.02642412

- Calculate the probability of getting 5 or more

successes.

Answer:

[1] 0.0327935

- What tail values would you use to test against the (two-sided)

null hypothesis that p=0.2? (Use qbinom() to get the answer,

and use pbinom(0:10,size=10,prob=0.2)

and pbinom(0:10,size=10,prob=0.2,lower.tail=FALSE) to check that your

answer makes sense.

You can use the R functions to test your understanding of

a distribution and make sure that random draws match up

with the theoretical distributions as they should.

This procedure is particularly valuable when you're developing new

probability distributions by combining simpler ones,

e.g. by zero-inflating or compounding distributions.

The results of a large number of random draws should have

the correct moments (mean and variance), and a histogram

of those random draws (with freq=FALSE or prob=TRUE)

should match up with the theoretical distribution.

For example, draws from a binomial distribution with

p=0.2 and N=20 should have a mean of approximately Np=4

and a variance of Np(1-p)=3.2:

> set.seed(1001)

> N = 20

> p = 0.2

> x = rbinom(10000, prob = p, size = N)

> c(mean(x), var(x))

[1] 4.001200 3.144913

The mean is very close, the variance

is a little bit farther off.

Just for the heck of it, we can use the

replicate() function to re-do this

command many times and see how close we get:

> var_dist = replicate(1000, var(rbinom(10000, prob = p, size = N)))

(this may take a little while; if it takes too long,

lower the number of replicates to 100).

Looking at the summary statistics and

at the 2.5% and 97.5% quantiles of the

distribution of variances:

> summary(var_dist)

Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

3.052 3.169 3.199 3.199 3.229 3.340

> quantile(var_dist, c(0.025, 0.975))

2.5% 97.5%

3.114357 3.285333

(Try a histogram too.)

Even though there's some variation (of

the variance) around the theoretical value,

we seem to be doing the right thing since

the 95% confidence limits include the theoretical

value.

(Lab 5 will go into more detail on running

simulations to check the expected variation

of different measurement as a function

of parameters and sample size.)

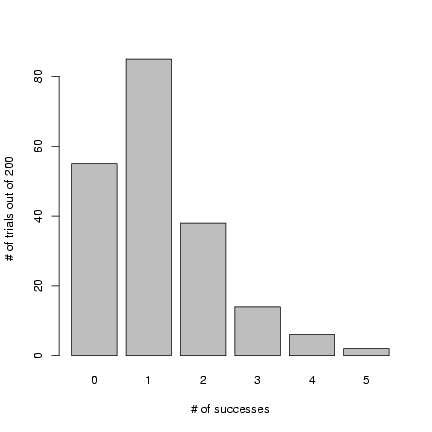

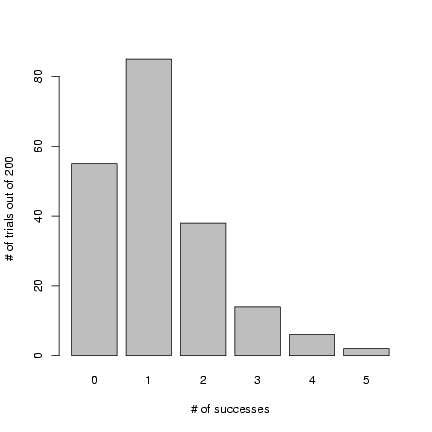

Finally, Figure 3 shows

the entire simulated frequency distribution

along with the theoretical values.

The steps in R are:

- pick 10,000 random deviates:

> x = rbinom(10000, prob = p, size = N)

- Tabulate the values, and divide

by the number of samples to get

a probability distribution:

> tx = table(factor(x, levels = 0:12))/10000

(The levels

command is necessary in this case

because the probability of

x=12 with p=0.2 and N=12

is actually so low (8.7×10-5)

that there's a reasonable chance that

a sample of 10,000 won't include any

samples with 12 successes.)

-

Draw a barplot of the values, extending

the y-limits a bit to make room for

the theoretical values and saving the

x locations at which the bars are drawn:

> b1 = barplot(tx, ylim = c(0, 0.23), ylab = "Probability")

- Add the theoretical values, plotting them

at the same x-locations as the centers

of the bars:

> points(b1, dbinom(0:12, prob = p, size = N), pch = 16)

(barplot() doesn't put the bars

at x locations corresponding to their

numerical values, so you have to save

those values as b1 and re-use

them to make sure the theoretical

values end up in the right place.)

A few alternative ways to do this plot would be:

-

> plot(factor(x))

> points(b1, 10000 * dbinom(0:12, prob = p, size = N))

(plots the number of observations without rescaling and

scales the probability distribution to match);

-

> plot(table(x)/10000)

> points(0:12, dbinom(0:12, prob = p, size = N))

Plotting a table does a plot with type="h" (high

density), which plots a vertical line for each value.

I think it's not quite as pretty as the barplot, but

it works.

Unlike factors, tables can be scaled numerically,

and the lines end up at the right numerical locations,

so we can just use 0:12 as the x locations

for the theoretical values.

- You could also draw a histogram:

since histograms were really designed

continuous data you have to make sure the

breaks occur in the right place (halfway

between counts):

> h = hist(x, breaks = seq(-0.5, 12.5, by = 1), col = "gray", prob = TRUE)

> points(0:12, dbinom(0:12, prob = p, size = N))

Figure 3: Checking binomial deviates against

theoretical values.

Doing the equivalent plot for continuous distributions

is actually somewhat easier, since you don't have

to deal with the complications of a discrete distribution:

just use hist(...,prob=TRUE) to show the

sampled distribution (possibly with ylim

adjusted for the maximum of the theoretical

density distribution) and

ddist(x,[parameters],add=TRUE) to add the

theoretical curve

(e.g.: curve(dgamma(x,shape=2,scale=1,add=FALSE))).

Exercise 2*:

Pick 10,000 negative binomial

deviates with m = 2, k=0.5.

Pick one of the ways above to draw

the distribution.

Check that the mean and variance

agree reasonably well with the theoretical values.

Add points representing

the theoretical distribution to the plot.

Now translate the m and k

parameters into their p and nn

equivalents (the coin-flipping derivation

of the negative binomial), and add

those points to the plot [use a different

plotting symbol to make sure you can see

that they overlap with the theoretical

values based on the m, k parameterization].

Figure 3: Checking binomial deviates against

theoretical values.

Doing the equivalent plot for continuous distributions

is actually somewhat easier, since you don't have

to deal with the complications of a discrete distribution:

just use hist(...,prob=TRUE) to show the

sampled distribution (possibly with ylim

adjusted for the maximum of the theoretical

density distribution) and

ddist(x,[parameters],add=TRUE) to add the

theoretical curve

(e.g.: curve(dgamma(x,shape=2,scale=1,add=FALSE))).

Exercise 2*:

Pick 10,000 negative binomial

deviates with m = 2, k=0.5.

Pick one of the ways above to draw

the distribution.

Check that the mean and variance

agree reasonably well with the theoretical values.

Add points representing

the theoretical distribution to the plot.

Now translate the m and k

parameters into their p and nn

equivalents (the coin-flipping derivation

of the negative binomial), and add

those points to the plot [use a different

plotting symbol to make sure you can see

that they overlap with the theoretical

values based on the m, k parameterization].

2 Averaging across discrete and continuous distributions

Suppose we have a (tiny) data set;

we can organize it in two different ways,

in standard long format or in tabular form:

> dat = c(5, 6, 5, 7, 5, 8)

> dat

[1] 5 6 5 7 5 8

> tabdat = table(dat)

> tabdat

dat

5 6 7 8

3 1 1 1

To get the (sample) probability distribution of the data,

just scale by the total sample size:

> prob = tabdat/length(dat)

> prob

dat

5 6 7 8

0.5000000 0.1666667 0.1666667 0.1666667

(dividing by sum(tabdat) would

be equivalent).

In the long format, we can take

the mean with mean(dat)

or, replicating the formula åxi/N

exactly, sum(dat)/length(dat).

In the tabular format, we

can calculate the mean

with the formula åP(x) x,

which in R would be

sum(prob*5:8) or

more generally

> vals = as.numeric(names(prob))

> sum(prob * vals)

[1] 6

(you could also get the values

by as.numeric(levels(prob)),

or by sort(unique(dat))).

However, mean(prob)

or mean(tabdat) is just plain wrong

(at least, I can't think of a situation where

you would want to calculate this value).

Exercise 3: figure out

what it means that

mean(tabdat) equals 1.5.

Going back the other way, from a table to raw values, we can use

the rep() function to repeat values an appropriate number of times.

In its simplest form, rep(x,n) just creates

a vector repeats x (which

may be either a single value or a vector) n times, but

if n is a vector as well then each element of x

is repeated the corresponding number of times: for example,

> rep(c(1, 2, 3), c(2, 1, 5))

[1] 1 1 2 3 3 3 3 3

gives two copies of 1, one copy of 2, and five copies of 3.

Therefore,

> rep(vals, tabdat)

[1] 5 5 5 6 7 8

will recover our original data (although not in the original

order) by repeating each element of vals

the correct number of times.

2.1 Jensen's inequality

Looking at Schmitt et al's data, the recruitment level very

nearly fits an exponential distribution with

a mean of 24.5 (so l = 1/24.5).

Schmitt et al. also say that recruitment (R)

as a function of settlement (S) is R = aS/(1+(a/b)S),

with a = 0.696 (initial slope, recruits per 0.1 m2 patch reef per recruit)

and b = 9.79 (asymptote, recruits per 0.1 m2 patch reef).

Let's see how strong Jensen's inequality is for this population.

We'll figure out the average by approximating an integral

by a sum: ò0¥ f(S) P(S) dS » åf(Si) P(Si) DS.

We need to set the range big enough to get most of the probability

of the distribution, and the DS small enough to get most

of the variation in the distribution; we'll try 0-200 in steps of 0.1.

(If I set the range too small or the DS too big, I'll miss

a piece of the distribution or the function. If I try to be too

precise, I'll waste time computing.)

In R:

> a = 0.696

> b = 9.79

> dS = 0.1

> S = seq(0, 200, by = dS)

> pS = dexp(S, rate = 1/24.5)

> fS = a * S/(1 + (a/b) * S)

> sum(pS * fS * dS)

[1] 5.008049

R also knows how to integrate functions numerically:

it can even approximate an integral from 0 to ¥.

First we have to define a (vectorizable) function:

> tmpf = function(S) {

+ dexp(S, rate = 1/24.5) * a * S/(1 + (a/b) * S)

+ }

Then we can just ask R to integrate it:

> i1 = integrate(tmpf, lower = 0, upper = Inf)

> i1

5.010691 with absolute error < 5.5e-05

(Use adapt(), in the adapt package,

if you need to do multidimensional integrals.)

This integral shows that we were pretty close

with our first approximation.

However, numerical integration will always

imply some level of approximation; be

careful with functions with sharp spikes,

because it can be easy to miss important parts

of the function.

Now to try out the delta function approximation:

> d1 = D(expression(a * x/(1 + (a/b) * x)), "x")

> d2 = D(d1, "x")

As stated above,

the mean value of the distribution is about 24.5.

The variance of the exponential distribution is

equal to the mean squared, or 600.25.

> Smean = 24.5

> Svar = Smean^2

> d2_num = eval(d2, list(a = 0.696, b = 9.79, x = Smean))

> mval = a * Smean/(1 + (a/b) * Smean)

> dapprox = mval + 1/2 * Svar * d2_num

> merr = (mval - i1$value)/i1$value

> merr

[1] 0.2412107

> err = (dapprox - i1$value)/i1$value

> err

[1] -0.04637931

The answer from the delta method

(f([`x])+(s2 f"([`x])/2))

is only about 5% below

the true value, as

opposed to the naive answer (f([`x])) which is about

25% high. (We have to say i1$value

to extract the actual value of the integral

from the variable i1; try str(i1)

if you want to see all the information that

R is storing about the integral.)

Exercise 4*:

try the above exercise again, but this time

with a gamma distribution instead of an exponential.

Keep the mean equal to 24.5 and change the

variance to 100, 25, and 1 (use the information

that the mean of the gamma distribution is shape*scale

and the variance is shape*scale^2).

Including the results for the exponential

(which is a gamma with shape=1), make a table

showing how the (1) true value of

mean recruitment [calculated by

numerical integration in R either

using integrate() or summing

over small DS] (2) value of

recruitment at the mean settlement

(3) delta-method approximation

(4,5) proportional error in #2 and #3

change with the variance.

3 The method of moments: reparameterizing distributions

In the chapter, I showed how to use the method of moments

to estimate the parameters of a distribution by setting the

sample mean and variance ([`x], s2) equal to the theoretical

mean and variance of a distribution and solving for the parameters.

For the negative binomial, in particular, I found m = [`x]

and k=([`x])/(s2/[`x] -1).

You can also define your own functions that use

your own parameterizations: call them my_function

rather than just replacing the standard R functions

(which will lead to insanity in the long run).

For example, defining

> my_dnbinom = function(x, mean, var, ...) {

+ mu = mean

+ k = mean/(var/mean - 1)

+ dnbinom(x, mu = mu, size = k, ...)

+ }

> my_rnbinom = function(n, mean, var, ...) {

+ mu = mean

+ k = mean/(var/mean - 1)

+ rnbinom(n, mu = mu, size = k, ...)

+ }

(the ... in the function takes any other arguments

you give to my_dnbinom and just passes them through,

unchanged, to dnbinom).

Defining your own functions can be handy if you need

to work on a regular basis with a distribution that

uses a different parameterization than the one built

into the standard R function.

You can use the kinds of histograms shown above to test your

results (remembering that the method of moments estimates

may be slightly biased especially for small samples - but

they shouldn't cause errors as large as those caused by

typical algebra mistakes).

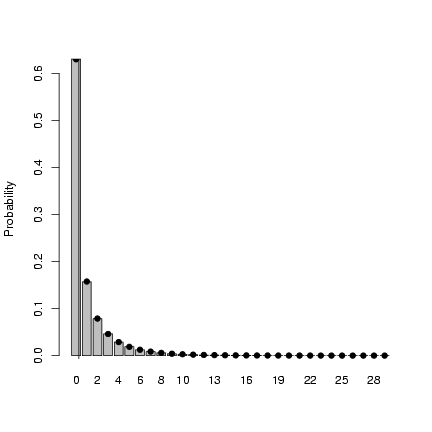

> x = my_rnbinom(1e+05, mean = 1, var = 4)

> mean(x)

[1] 0.9999

> var(x)

[1] 4.00574

> tx = table(factor(x, levels = 0:max(x)))/1e+05

> b1 = barplot(tx, ylab = "Probability")

> points(b1, my_dnbinom(0:max(x), mean = 1, var = 4), pch = 16)

> abline(v = 1)

Exercise 5*:

Morris (1997) gives a definition of the beta function that

is different from the standard statistical parameterization.

The standard parameterization is

Exercise 5*:

Morris (1997) gives a definition of the beta function that

is different from the standard statistical parameterization.

The standard parameterization is

|

Beta(x|a,b) = |

G(a+b)

G(a)G(b)

|

xa-1(1-x)b-1 |

|

whereas Morris uses

|

Beta(x|P,q) = |

G(q)

G(qP)G(q(1-P))

|

xqP-1 (1-x)q(1-P)-1. |

|

Find expressions for P and q in terms of a and b

and vice versa. Explain why you might prefer Morris's

parameterization.

Define a new set of functions that generate random

deviates from the beta distribution (my_rbeta)

and calculate the density function (my_dbeta)

in terms of P and q.

Generate a histogram from this distribution

and draw a vertical line showing the mean of the distribution.

4 Creating new distributions

4.1 Zero-inflated distributions

The general formula for the probability distribution of

the a zero-inflated distribution, with an underlying

distribution P(x) and a zero-inflation probability

of pz, is:

So, for example, we could define a probability distribution

for a zero-inflated negative binomial as follows:

> dzinbinom = function(x, mu, size, zprob) {

+ ifelse(x == 0, zprob + (1 - zprob) * dnbinom(0, mu = mu,

+ size = size), (1 - zprob) * dnbinom(x, mu = mu, size = size))

+ }

(the name, dzinbinom, follows the R convention

for a probability distribution function: a d

followed by the abbreviated name of the distribution,

in this case zinbinom for

"zero-inflated negative

binomial").

The ifelse() command checks every element of

x to see whether it is zero or not and fills

in the appropriate value depending on the answer.

A random deviate generator would look like this:

> rzinbinom = function(n, mu, size, zprob) {

+ ifelse(runif(n) < zprob, 0, rnbinom(n, mu = mu, size = size))

+ }

The command runif(n) picks n

random values between 0 and 1; the ifelse

command compares them with the value of

zprob. If an individual value is

less than zprob (which happens with probability

zprob=pz), then the corresponding

random number is zero; otherwise it is a value

picked out of the appropriate negative binomial

distribution.

Exercise 6:

check graphically that these functions actually

work. For an extra challenge, calculate the mean

and variance of the zero-inflated negative binomial

and compare it to the results of

rzinbinom(10000,mu=4,size=0.5,zprob=0.2).

5 Compounding distributions

The key to compounding distributions in R is

that the functions that generate random deviates

can all take a vector of different parameters

rather than a single parameter. For example,

if you were simulating the number of hatchlings

surviving (with individual probability 0.8)

from a series of 8 clutches, all of size

10, you would say

> rbinom(8, size = 10, prob = 0.8)

[1] 7 6 9 7 9 9 6 8

but if you had a series of clutches

of different sizes, you could still

pick all the random values at the same time:

> clutch_size = c(10, 9, 9, 12, 10, 10, 8, 11)

> rbinom(8, size = clutch_size, prob = 0.8)

[1] 10 7 8 8 6 7 6 8

Taking this a step farther, the clutch size

itself could be a random variable:

> clutch_size = rpois(8, lambda = 10)

> rbinom(8, size = clutch_size, prob = 0.8)

[1] 7 10 7 11 13 4 5 4

We've just generated a Poisson-binomial

random deviate ...

As a second example, I'll

follow Clark et al. in constructing

a distribution that is a compounding

of normal distributions, with 1/variance of each sample drawn from

a gamma distribution.

First pick the variances as the reciprocals of 10,000 values

from a gamma distribution with shape 5 (setting the scale equal

to 1/5 so the mean will be 1):

> var_vals = 1/rgamma(10000, shape = 5, scale = 1/5)

Take the square root, since dnorm uses

the standard deviation and not the variance

as a parameter:

> sd_vals = sqrt(var_vals)

Generate 10,000 normal deviates using this

range of standard deviations:

> x = rnorm(10000, mean = 0, sd = sd_vals)

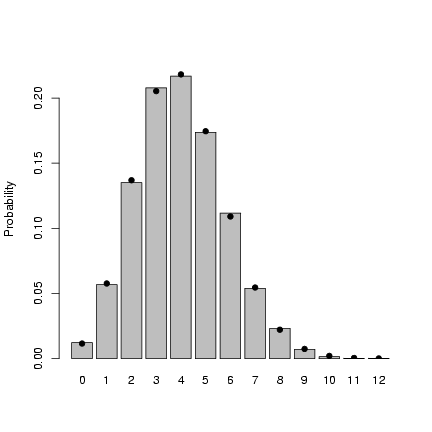

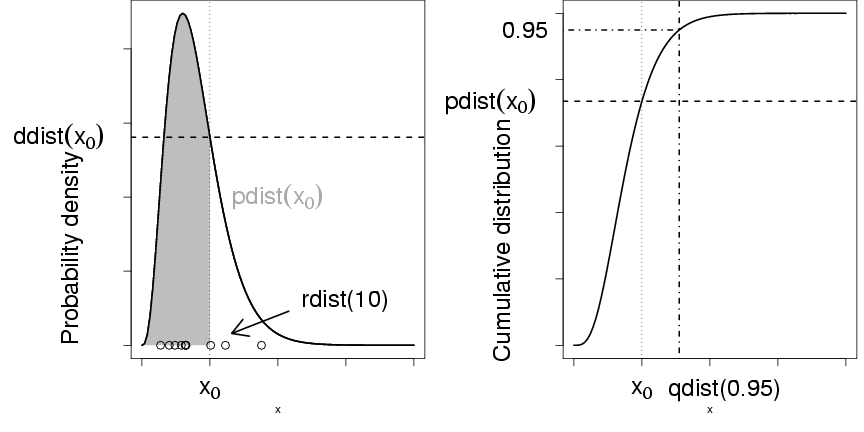

Figure 4 shows a histogram of the

following commands:

> hist(x, prob = TRUE, breaks = 100, col = "gray")

> curve(dt(x, df = 11), add = TRUE, lwd = 2)

The superimposed curve is a t distribution

with 11 degrees of freedom; it turns out that

if the underlying gamma distribution has

shape parameter p, the resulting t distribution

has df=2p+1.

(Figuring out the analytical form of the compounded

probability distribution or density function, or

its equivalence to some existing distribution,

is the hard part; for the most part, though,

you can find these answers in the ecological

and statistical literature if you search hard

enough.

> hist(x, prob = TRUE, breaks = 100, col = "gray")

> curve(dt(x, df = 11), add = TRUE, lwd = 2)

Figure 4: Clark model: inverse gamma compounded with normal,

equivalent to the Student t distribution

Exercise 7*:

generate 10,000 values from

a gamma-Poisson compounded distribution

with parameters shape=k=0.5, scale=m/k=4/0.5=8

and demonstrate that it's equivalent to a

negative binomial with the appropriate

m and k parameters.

Extra credit: generate 10,000

values from a lognormal-Poisson distribution

with the same expected mean and variance

(the variance of the lognormal should

equal the variance of the gamma distribution

you used as a compounding distribution;

you will have to do some algebra

to figure out the values of meanlog

and sdlog needed to produce a lognormal

with a specified mean and variance.

Plot the distribution and superimpose

the theoretical distribution of the

negative binomial with the same mean

and variance

to see how different the shapes of the distributions

are.

Figure 4: Clark model: inverse gamma compounded with normal,

equivalent to the Student t distribution

Exercise 7*:

generate 10,000 values from

a gamma-Poisson compounded distribution

with parameters shape=k=0.5, scale=m/k=4/0.5=8

and demonstrate that it's equivalent to a

negative binomial with the appropriate

m and k parameters.

Extra credit: generate 10,000

values from a lognormal-Poisson distribution

with the same expected mean and variance

(the variance of the lognormal should

equal the variance of the gamma distribution

you used as a compounding distribution;

you will have to do some algebra

to figure out the values of meanlog

and sdlog needed to produce a lognormal

with a specified mean and variance.

Plot the distribution and superimpose

the theoretical distribution of the

negative binomial with the same mean

and variance

to see how different the shapes of the distributions

are.

File translated from

TEX

by

TTH,

version 3.67.

On 28 Sep 2005, 13:38.

Exercise 5*:

Morris (1997) gives a definition of the beta function that

is different from the standard statistical parameterization.

The standard parameterization is

Exercise 5*:

Morris (1997) gives a definition of the beta function that

is different from the standard statistical parameterization.

The standard parameterization is