Exploratory data analysis and graphics: lab 2

© 2005 Ben Bolker

This lab will cover many if not all of the

details you actually need to know about R to

read in data and produce the figures shown in

Chapter 2, and more.

The exercises, which will be considerably more

difficult than those in Lab 1, will typically

involve variations on the figures shown in the

text. You will work through reading in

the different data sets and constructing the

figures shown, or variants of them. It would

be even better to work through reading in

and making exploratory plots of your own data.

1 Reading data

Find the file called seedpred.dat:

it's in the right format (plain text, long format),

so you can just read it in with

> data = read.table("seedpred.dat", header = TRUE)

(remember not to copy the > if you

are cutting and pasting from this document).

Add the variable available

to the data frame by

combining taken and remaining

(using the $ symbol):

> data$available = data$taken + data$remaining

Pitfall #1: finding your file

If R responds to your read.table() or

read.csv() command

with an error like

Error in file(file, "r") : unable to open connection

In addition: Warning message: cannot open file 'myfile.csv'

it means it can't find your file, probably because it isn't looking in the right place.

By default, R's working directory is the directory in which

the R program starts up, which is (again by default) something like

C:/Program Files/R/rw2010/bin. ( R uses /

as the [operating-system-independent]

separator between directories in a file path.)

The simplest way to change this for the duration of your R session

is to go to File/Change dir ..., click on the Browse

button, and move to your Desktop (or wherever your file is located).

You can also use the setwd() command to set the

working directory (getwd() tells you what

the current working directory is).

While you could just throw everything on your desktop,

it's good to get in the habit of setting up a

separate working directory for different projects, so that

your data files, metadata files, R script files, and so forth, are all in

the same place.

Depending on how you have gotten your data files onto your system

(e.g. by downloading them from the web), Windows

will sometimes hide or otherwise screw up the extension of your

file (e.g. adding .txt to a file called mydata.dat).

R needs to know the full name of the file, including the extension.

Pitfall #2: checking number of fields

The next potential problem is that R needs every line of your data file to have the

same number of fields (variables). You may get an error like:

Error in read.table(file = file, header = header, sep = sep, quote = quote, :

more columns than column names

or

Error in scan(file = file, what = what, sep = sep, quote = quote, dec = dec, :

line 1 did not have 5 elements

If you need to check on the number of fields that

R thinks you have on each line, use

> count.fields("myfile.dat", sep = ",")

(you can omit the sep="," argument if

you have whitespace- rather than comma-delimited

data).

If you are checking a long data file you can try

> cf = count.fields("myfile.dat", sep = ",")

> which(cf != cf[1])

to get the line numbers with numbers of fields

different from the first line.

By default R will try to fill in what it sees

as missing fields with NA ("not available")

values; this can be useful but can also hide

errors. You can try

> mydata <- read.csv("myfile.dat", fill = FALSE)

to turn off this behavior; if you don't

have any missing fields at the end of lines

in your data this should work.

1.1 Checking data

Here's the quickest way to check that all your variables have

been classified correctly:

> sapply(data, class)

Species tcum tint remaining taken available

"factor" "integer" "integer" "integer" "integer" "integer"

(this applies the class() command, which identifies

the type of a variable, to each column in your data).

Non-numeric missing-variable strings

(such as a star, *) will also make R

misclassify. Use na.strings

in your read.table() command:

> mydata <- read.table("mydata.dat", na.strings = "*")

(you can specify more than one value with (e.g.)

na.strings=c("*","***","bad","-9999")).

Exercise 1: Try out

head(), summary() and str()

on data; make sure you understand the results.

1.2 Reshaping data

It's hard to give an example of reshaping the

seed predation data set because we have

different numbers of observations for each

species - thus, the data won't fit nicely

into a rectangular format with (say) all

observations from each species on the same

line.

However, as in the chapter text I can

just make up a data frame and reshape it.

Here are the commands to generate the

data frame I used as

an example in the text (I use LETTERS,

a built-in vector of the capitalized letters

of the alphabet, and runif(), which

picks a specified number of random numbers

from a uniform distribution between 0 and 1.

The command round(x,3)

rounds x to 3 digits after the decimal place.):

> loc = factor(rep(LETTERS[1:3], 2))

> day = factor(rep(1:2, each = 3))

> val = round(runif(6), 3)

> d = data.frame(loc, day, val)

This data set is in long format.

To go to wide format:

> d2 = reshape(d, direction = "wide", idvar = "loc", timevar = "day")

> d2

loc val.1 val.2

1 A 0.362 0.598

2 B 0.522 0.692

3 C 0.722 0.697

idvar="loc" specifies

that loc is the

identifier that should be used to assign multiple

values to the same row,

and timevar="day" specifies which variable

can be lumped together on the same row.

To go back to long format:

> reshape(d2, direction = "long", varying = c("val.1", "val.2"),

+ timevar = "day", idvar = "loc")

loc day val

A.1 A 1 0.362

B.1 B 1 0.522

C.1 C 1 0.722

A.2 A 2 0.598

B.2 B 2 0.692

C.2 C 2 0.697

varying specifies which variables are changing

and need to be reshaped, and timevar

specifies the name of the variable to be (re)created

to distinguish different samples in the same location.

Exercise 2: unstack() works with

a formula. Try unstack(d,val~day) and

unstack(d,val~loc) and figure out what's going on.

1.3 Advanced data types

While you can usually get by coding data in

not quite the right way - for example, coding dates

as numeric values or categorical variables as

strings - R tries to "do the right

thing" with your data, and it is more likely to

do the right thing the more it knows about how your

data are structured.

Strings instead of factors

Sometimes R's default of assigning factors is not what you want: if

your strings are unique identifiers (e.g. if you have a code for

observations that combines the date and location of sampling, and each

location combination is only sampled once on a given date) then R's

strategy of coding unique levels as integers and then associating a

label with integers will waste space and add confusion.

If all of your non-numeric variables should be treated

as character strings rather than factors, you can just

specify as.is=TRUE; if you want specific columns

to be left "as is" you can specify them by number or column

name. For example, these two commands have the same result:

> data2 = read.table("seedpred.dat", header = TRUE, as.is = "Species")

> data2 = read.table("seedpred.dat", header = TRUE, as.is = 1)

> sapply(data2, class)

Species tcum tint remaining taken

"character" "integer" "integer" "integer" "integer"

(use c() - e.g. c("name1","name2") or c(1,3) -

to specify more than one column).

You can also use the colClasses="character" argument to

read.table() to specify that a particular column should

be converted to type character -

> data2 = read.table("seedpred.dat", header = TRUE, colClasses = c("character",

+ rep("numeric", 4)))

again has the same results as the commands above.

To convert factors back to strings after you have read them

into R, use as.character().

> data2 = read.table("seedpred.dat", header = TRUE)

> sapply(data2, class)

Species tcum tint remaining taken

"factor" "integer" "integer" "integer" "integer"

> data2$Species = as.character(data2$Species)

> sapply(data2, class)

Species tcum tint remaining taken

"character" "integer" "integer" "integer" "integer"

Factors instead of numeric values

In contrast, sometimes you have numeric labels for data

that are really categorical values - for example if your

sites or species have integer codes (often data sets

will have redundant information in them, e.g. both

a species name and a species code number).

It's best to specify appropriate data types, so use

colClasses to force R to treat the data as

a factor. For example, if we wanted to make tcum

a factor instead of a numeric variable:

> data2 = read.table("seedpred.dat", header = TRUE, colClasses = c(rep("factor",

+ 2), rep("numeric", 3)))

> sapply(data2, class)

Species tcum tint remaining taken

"factor" "factor" "numeric" "numeric" "numeric"

n.b.: by default, R sets the order of the

factor levels alphabetically.

You can find out the levels and their order

in a factor f with levels(f).

If you want

your levels ordered in some other way (e.g. site

names in order along some transect), you need to

specify this explicitly. Most confusingly,

R will sort strings in alphabetic order too,

even if they represent numbers.

This is OK:

> f = factor(1:10)

> levels(f)

[1] "1" "2" "3" "4" "5" "6" "7" "8" "9" "10"

but this is not, since we explicitly tell R to treat the numbers as characters (this can

happen by accident in some contexts):

> f = factor(as.character(1:10))

> levels(f)

[1] "1" "10" "2" "3" "4" "5" "6" "7" "8" "9"

In a list of numbers from 1 to 10, "10"

comes after "1" but before "2" ...

You can fix the levels by using the

levels argument in factor()

to tell R explicitly

what you want it to do, e.g.:

> f = factor(as.character(1:10), levels = 1:10)

> x = c("north", "middle", "south")

> f = factor(x, levels = c("far_north", "north", "middle", "south"))

so that the levels come out ordered geographically

rather than alphabetically.

Sometimes your data contain a subset of integer

values in a range, but you want to make sure the

levels of the factor you construct include all

of the values in the range, not just the ones

in your data. Use levels again:

> f = factor(c(3, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10), levels = 3:10)

Finally, you may want to get rid of levels that

were included in a previous factor but are no

longer relevant:

> f = factor(c("a", "b", "c", "d"))

> f2 = f[1:2]

> levels(f2)

[1] "a" "b" "c" "d"

> f2 = factor(as.character(f2))

> levels(f2)

[1] "a" "b"

For more complicated operations with

factor(), use the recode()

function in the car package.

Exercise 3:

Illustrate the effects of the levels

command by plotting the factor f=factor(c(3,3,5,6,7,8,10))

as created with and without intermediate levels.

For an extra challenge, draw them as two side-by-side

subplots. (Use par(mfrow=c(1,1)) to restore

a full plot window.)

Dates

Dates and times can be tricky in R, but you can (and should)

handle your dates as type Date

within R rather than messing around

with Julian days (i.e., days since the

beginning of the year) or maintaining

separate variables for day/month/year.

You can use colClasses="Date"

within read.table() to read in

dates directly from a file, but only if

your dates are in four-digit-year/month/day

(e.g. 2005/08/16 or 2005-08-16) format;

otherwise R will either butcher your

dates or complain

Error in fromchar(x) : character string is not in a standard unambiguous format

If your dates are in another format in

a single column, read them in as character

strings (colClasses="character" or

using as.is) and then use as.Date(),

which uses a very flexible format argument

to convert character formats to dates:

> as.Date(c("1jan1960", "2jan1960", "31mar1960", "30jul1960"),

+ format = "%d%b%Y")

[1] "1960-01-01" "1960-01-02" "1960-03-31" "1960-07-30"

> as.Date(c("02/27/92", "02/27/92", "01/14/92", "02/28/92", "02/01/92"),

+ format = "%m/%d/%y")

[1] "1992-02-27" "1992-02-27" "1992-01-14" "1992-02-28" "1992-02-01"

The most useful format codes are %m for month number,

%d for day of month, %j% for Julian date (day of year),

%y% for two-digit year (dangerous for dates before 1970!)

and %Y% for four-digit year; see ?strftime for

many more details.

If you have your dates as separate (numeric) day, month, and year

columns, you actually have to squash them together into a

character format (with paste(), using

sep="/" to specify that the values should be separated

by a slash) and then convert them to dates:

> year = c(2004, 2004, 2004, 2005)

> month = c(10, 11, 12, 1)

> day = c(20, 18, 28, 17)

> datestr = paste(year, month, day, sep = "/")

> date = as.Date(datestr)

> date

[1] "2004-10-20" "2004-11-18" "2004-12-28" "2005-01-17"

Although R prints the

dates out so they look like a vector of character strings,

they are really dates: class(date) will

give you the answer "Date".

Other traps:

1.4 Accessing data and extra packages

Data

To access individual variables within your data set use

mydata$varname or mydata[,n] or

mydata[,"varname"] where n is the column number and

varname is the variable name you want. You can also use

attach(mydata) to set things up so that you can refer to the

variable names alone (e.g. varname rather than

mydata$varname). However, beware: if you then modify

a variable, you can end up with two copies of it: one (modified) is a

local variable called varname, the other (original) is a column

in the data frame called varname: it's probably better not to

attach a data set until after you've finished cleaning and

modifying it. Furthermore, if you have already created a variable

called varname, R will find it before it finds the version of

varname that is part of your data set. Attaching multiple

copies of a data set is a good way to get confused: try to remember

to detach(mydata) when you're done.

I'll start by attaching the data set (so

we can refer to Species instead of

data$Species and so on).

> attach(data)

To access data that are built in to R or included

in an R package (which you probably won't need to

do often), say

> data(dataset)

(data() by itself will list all available data sets.)

Packages

The sizeplot() function

I used for Figure 2 in the chapter requires an add-on package

(unfortunately the command for loading a package

is library()!). To use

an additional package it must

be (i) installed on your machine

(with install.packages()) or

through the menu system and (ii) loaded in your

current R session (with library()).

> install.packages("plotrix")

> library(plotrix)

You must both install and

load a package before you can use

or get help on its functions, although help.search()

will list functions in packages that are installed but not yet

loaded.

2 Exploratory graphics

2.1 Bubble plot

> sizeplot(available, taken, xlab = "Available", ylab = "Taken")

will give you approximately the same basic graph shown in the chapter,

although I also played around with the x- and y-limits

(using xlim and ylim) and the axes. (The basic

procedure for showing custom axes in R is to turn off the

default axes by specifying axes=FALSE and then to

specify the axes one at a time with the axis() command.)

I used

> t1 = table(available, taken)

to cross-tabulate the data,

and then used the text()

command to add the numbers to the plot.

There's a little bit

more trickery involved in

putting the numbers in the right place on the plot. row(x) gives a matrix with

the row numbers corresponding to the elements of x; col(x)

does the same for column numbers. Subtracting 1 (col(x)-1)

accounts for the fact that columns 1 through 6 of our table refer to 0 through 5

seeds actually taken. When R plots, it simply matches up each

of the x values, each of the y values, and each of the text

values (which in this case are the numbers in the table) and plots

them, even though the numbers are arranged in matrices rather

than vectors.

I also limit the plotting to positive values (using [t1>0]),

although this is just cosmetic.

> r = row(t1)

> c = col(t1) - 1

> text(r[t1 > 0], c[t1 > 0], t1[t1 > 0])

is the final version of the commands.

2.2 Barplot

The command to produce the barplot (Figure 3) was:

> barplot(t(log10(t1 + 1)), beside = TRUE, legend = TRUE, xlab = "Available",

+ ylab = "log10(1+# observations)")

> op = par(xpd = TRUE)

> text(34.5, 3.05, "Number taken")

> par(op)

As mentioned in the text, log10(t1+1) finds

log(x+1), a reasonable transformation to compress

the range of discrete data; t() transposes

the table so we can plot groups by number available.

The beside=TRUE argument plots grouped rather

than stacked bars; legend=TRUE plots a legend;

and xlab and ylab set labels.

The statement par(xpd=TRUE) allows text and

lines to be plotted outside the edge of the plot;

the op=par(...) and par(op) are a way

to set parameters and then restore the original settings

(I could have called op anything I wanted, but

in this case it stands for old parameters).

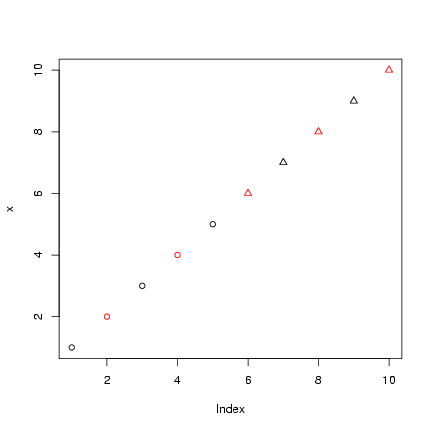

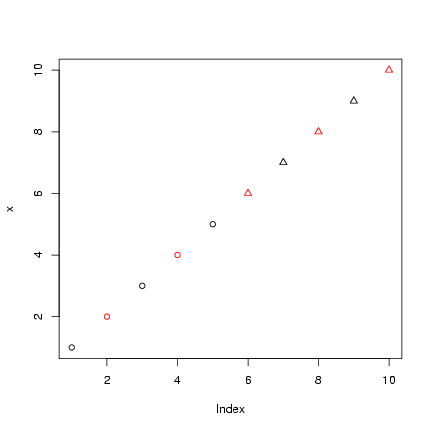

Exercise 4*:

In general, you can specify plotting characters

and colors in parallel with your data, so that

different points get plotted with different

plotting characters and colors.

For example:

> x = 1:10

> col_vec = rep(1:2, length = 10)

> pch_vec = rep(1:2, each = 5)

> plot(x, col = col_vec, pch = pch_vec)

Take the old tabular data (t1), log(1+x)-transform them,

and use as.numeric() to drop

all the information in tabular form

and convert them to a numeric

vector.

Plot them (plotting the data numeric vector

will generate a scatterplot of values on the

y-axis vs. observation number on the x-axis),

color-coded according to the

number available (rows) and point-type-coded

according the number taken (columns: note, there

is no color 0, so don't subtract 1).

order(x) is a function that gives a vector

of integers that will put x in increasing

order. For example, if I set x=c(3,1,2)

then order(z) is 2 3 1: putting

the second element first, the third element

second, and the first element last will

put the vector in increasing order.

In contrast, rank(x) just gives

the ranks

y[order(x)] sorts y by

the elements of x.

Redo the plot with

the data sorted in increasing order; make sure

the colors and point types match the data properly.

Does this way of plotting the data show anything

the bubbleplot didn't? Can you think of other ways

of plotting these data?

Take the old tabular data (t1), log(1+x)-transform them,

and use as.numeric() to drop

all the information in tabular form

and convert them to a numeric

vector.

Plot them (plotting the data numeric vector

will generate a scatterplot of values on the

y-axis vs. observation number on the x-axis),

color-coded according to the

number available (rows) and point-type-coded

according the number taken (columns: note, there

is no color 0, so don't subtract 1).

order(x) is a function that gives a vector

of integers that will put x in increasing

order. For example, if I set x=c(3,1,2)

then order(z) is 2 3 1: putting

the second element first, the third element

second, and the first element last will

put the vector in increasing order.

In contrast, rank(x) just gives

the ranks

y[order(x)] sorts y by

the elements of x.

Redo the plot with

the data sorted in increasing order; make sure

the colors and point types match the data properly.

Does this way of plotting the data show anything

the bubbleplot didn't? Can you think of other ways

of plotting these data?

You can use barchart() in the lattice package

to produce these graphics,

although it seems impossible to turn the graph so the

bars are vertical. Try the following (stack=FALSE

is equivalent to beside=TRUE for barplot()):

> library(lattice)

> barchart(log10(1 + table(available, taken)), stack = FALSE, auto.key = TRUE)

More impressively, the lattice package

can automatically plot a barplot of a three-way

cross-tabulation, in small multiples (I had to experiment

a bit to get the factors in the right order in the

table() command): try

> barchart(log10(1 + table(available, Species, taken)), stack = FALSE,

+ auto.key = TRUE)

Exercise 5*:

Restricting your analysis to only the observations with

5 seeds available, create a barplot showing

the distribution of number of seeds taken broken down by species.

Hints: you can create a new data set that includes only

the appropriate rows by using row indexing, then attach()

it.

2.3 Barplot with error bars

Computing the fraction taken:

> frac_taken = taken/available

Computing the mean fraction taken

for each number of seeds available,

using the tapply()

function:

tapply() ("table apply",

pronounced "t apply"), is an extension of the table()

function; it splits a specified vector into groups according to

the factors provided, then applies a function (e.g.

mean() or sd()) to each group.

This idea of applying a function to a set of objects is a very general,

very powerful idea in data manipulation with R; in due

course we'll learn about apply() (apply a function

to rows and columns of matrices), lapply() (apply

a function to lists), sapply() (apply a function

to lists and simplify), and mapply() (apply a function

to multiple lists).

For the present, though,

> mean_frac_by_avail = tapply(frac_taken, available, mean)

computes the mean of frac_taken for each group defined

by a different value of available ( R automatically

converts available into a factor temporarily for this

purpose).

If you want to compute the mean by group for more than

one variable in a data set, use aggregate().

We can also calculate the standard errors,

s/Ön:

> n_by_avail = table(available)

> se_by_avail = tapply(frac_taken, available, sd)/sqrt(n_by_avail)

I'll actually use a variant of barplot(),

barplot2() (from the gplots package,

which you may need to install,

along with the

the gtools and gdata

packages) to plot these values

with standard errors. (I am mildly embarrassed that

R does not supply error-bar plotting as a built-in function,

but you can use the barplot2()

in the gplots package or the plotCI() function

(the gplots and plotrix packages have slightly

different versions).

> library(gplots)

> lower_lim = mean_frac_by_avail - se_by_avail

> upper_lim = mean_frac_by_avail + se_by_avail

> b = barplot2(mean_frac_by_avail, plot.ci = TRUE, ci.l = lower_lim,

+ ci.u = upper_lim, xlab = "Number available", ylab = "Mean number taken")

I specified that I wanted error bars plotted

(plot.ci=TRUE) and the lower (ci.l) and

upper (ci.u) limits.

2.4 Histograms by species

All I had to do to get the lattice package to

plot the histogram by species was:

> histogram(~frac_taken | Species, xlab = "Fraction taken")

It's possible to do this with base graphics, too,

but you have to rearrange your data yourself:

essentially, you have to split the data up by

species, tell R to break the plotting area

up into subplots, and then tell R to draw a histogram

in each subplot.

- To reorganize the data appropriately and

draw the plot, I first use split(), which cuts a vector into a list

according to the levels of a factor - in this

case giving us a list of the fraction-taken data

separated by species:

> splitdat = split(frac_taken, Species)

- Next I use the par()

command

> op = par(mfrow = c(3, 3), mar = c(2, 2, 1, 1))

to specify a 3 × 3 array

of mini-plots (mfrow=c(3,3)) and to reduce

the margin spacing to 2 lines on the bottom and left

sides and 1 line on the top and right

(mar=c(2,2,1,1)).

- Finally, I combine

lapply(), which

applies a command to each of the

elements in a list,

with the hist()

(histogram) command.

You can specify extra arguments in lapply()

that will be passed along to the hist() function - in this

case they're designed to strip out unnecessary detail

and make the subplots bigger.

> h = lapply(splitdat, hist, xlab = "", ylab = "", main = "", col = "gray")

Assigning the answer to a variable stops R from printing

the results, which I don't really want to see in this case.

-

par(op) will restore the previous

graphics parameters.

It's a bit harder to get the species names plotted on the

graphs: it is technically possible to use mapply()

to do this, but then we've reinvented most of the wheels

used in the lattice version ...

Plots in this section:

scatterplot (plot() or xyplot())

bubble plot (sizeplot()),

barplot (barplot() or barchart() or barplot2()),

histogram (hist() or histogram()).

Data manipulation:

reshape(), stack()/unstack(), table(),

split(), lapply(), sapply()

3 Measles data

I'm going to clear the workspace (rm(list=ls())

lists all the objects in the workspace with ls() and

then uses rm() to remove them: you can also

Clear workspace from the menu) and read in the

measles data, which are space-separated and have

a header:

> detach(data)

> rm(list = ls())

> data = read.table("ewcitmeas.dat", header = TRUE, na.strings = "*")

> attach(data)

year, mon, and day were read in as integers:

I'll create a date variable as described above.

For convenience, I'm also defining a variable with

the city names.

> date = as.Date(paste(year + 1900, mon, day, sep = "/"))

> city_names = colnames(data)[4:10]

Later on it will be useful to have the data in long

format. It's easiest to do use stack() for

this purpose (data.long = stack(data[,4:10])),

but that wouldn't preserve the date information.

As mentioned in the chapter, reshape()

is trickier but more flexible:

> data = cbind(data, date)

> data_long = reshape(data, direction = "long", varying = list(city_names),

+ v.name = "incidence", drop = c("day", "mon", "year"), times = factor(city_names),

+ timevar = "city")

3.1 Multiple-line plots

matplot() (matrix plot),

which plots several different numeric variables on a common

vertical axis, is most useful when we have a

wide format (otherwise it wouldn't make sense

to plot multiple columns on the same scale).

I'll plot columns 4 through 10, which

represent the incidence data, against the date, and I'll

tell R to use lines (type="l"), and to plot all lines

in different colors with different line types

(the colors aren't very useful since I have set

them to different gray scales for printing purposes,

but the example

should at least give you the concept). I also have to

tell it not to put on any axes, because R won't

automatically plot a date axis. Instead, I'll

use the axis() and axis.Date() commands to

add appropriate axes to the left (side=2) and

bottom (side=1) sides of the plot, and then

use box() to draw a frame around the plot.

I've used abline() to add vertical lines (v=) to

the plot every two years, and also

on 1 January 1968 (approximately when mass vaccination

against measles began in the UK). You can also use

abline() to add

horizontal lines (h=); or lines with

intercepts (a=) and slopes (b=).

(I use seq.Date(), a special command to

create a sequence of dates, to define the beginning

of biennial periods.)

legend() puts a legend on the plot; I set

the line width (lwd to 2 so you could actually

see the different colors.

Here are the commands:

> matplot(date, data[, 4:10], type = "l", col = 1:7, lty = 1:7,

+ axes = FALSE, ylab = "Weekly incidence", xlab = "Date")

> axis(side = 2)

> axis.Date(side = 1, x = date)

> vacc.date = as.Date("1968/1/1")

> biennial = seq.Date(as.Date("1948/9/1"), as.Date("1986/9/1"),

+ by = "2 years")

> abline(v = biennial, col = "gray", lty = 2)

> abline(v = vacc.date, lty = 2, lwd = 2)

> legend(x = 1970, y = 5000, city_names, col = 1:7, lty = 1:7,

+ lwd = 2, bg = "white")

> box()

I could use the long-format data set

and the lattice package to do

this more easily, although without the refinements of a date

axis, using

> xyplot(incidence ~ date, groups = city, data = data_long, type = "l",

+ auto.key = TRUE)

To plot each city in its own subplot,

use the formula incidence~date|city and omit the groups argument.

You can also draw any of these plots with different kinds of symbols

("l" for lines, "p" for points (default): see

?plot for other options).

3.2 Histogram and density plots

I'll start by just collapsing all the incidence data into a

single, logged, non-NA vector (in this case

I have to use c(as.matrix(x)) to collapse the data and remove

all of the data frame information):

> allvals = na.omit(c(as.matrix(data[, 4:10])))

> logvals = log10(1 + allvals)

The histogram (hist() command is fairly easy: the only tricks are to

leave room for the other lines that will go on the plot by

setting the y limits with ylim, and to specify that

we want the data plotted as relative frequencies, not numbers

of counts (freq=FALSE or prob=TRUE). This option

tells R to divide by total number of counts and then by the bin width,

so that the area covered by all the bars adds up to 1; this scaling

makes the vertical scale of the histogram compatible with a density plot, or among different

histograms with different number of counts or bin widths

(?? include in chapter ??).

> hist(logvals, col = "gray", main = "", xlab = "Log weekly incidence",

+ ylab = "Density", freq = FALSE, ylim = c(0, 0.6))

Adding lines for the density is straightforward, since R knows

what to do with a density object - in general, the lines

command just adds lines to a plot.

> lines(density(logvals), lwd = 2)

> lines(density(logvals, adjust = 0.5), lwd = 2, lty = 2)

Adding the estimated normal distribution

requires a couple of new functions:

- dnorm()

computes the probability density function of the

normal distribution with a specified mean and

standard deviation (much more on this in

Chapter 4).

- curve() is a magic function for

drawing a theoretical curve

(or, if add=TRUE, adding one to an existing

plot) . The magic part is

that your curve must be expressed in terms

of x; curve(x^22*x)+ will work,

but curve(y^22*y)+ won't. You can specify

other graphics parameters (line type (lty)

and width (lwd) in this case).

> curve(dnorm(x, mean = mean(logvals), sd = sd(logvals)), lty = 3,

+ lwd = 2, add = TRUE)

By now the legend() command should be reasonably

self-explanatory:

> legend(x = 2.1, y = 0.62, legend = c("density, default", "density, adjust=0.5",

+ "normal"), lwd = 2, lty = c(1, 2, 3))

3.3 Scaling data

Scaling the incidence in each city by the population size,

or by the mean or maximum incidence in that city, begins

to get us into some non-trivial data manipulation.

This process may actually be easier in the wide format.

Several useful commands:

- rowMeans(), rowSums(), colMeans(),

and colSums() will compute the means or sums of columns

efficiently. In this case we would do something like

colMeans(data[,4:10]) to get the mean incidence for

each city.

- apply() is the more general command for running

some command on each of a set of rows or columns. When you

look at the help for apply() you'll see an argument

called MARGIN, which specifies whether you want

to operate on rows (1) or columns (2). For example,

apply(data[,4:10],1,mean) is the equivalent

of rowMeans(data[,4:10]), but we can also easily

say (e.g.) apply(data[,4:10],1,max) to get the

maxima instead. Later, when you've gotten practice

defining your own functions, you can apply any function - not

just R's built-in functions.

- scale() is a function for subtracting and dividing

specified amounts out of the columns of a matrix. It is fairly

flexible: scale(x,center=TRUE,scale=TRUE) will center by

subtracting the means and then

scale by dividing by the standard errors of the columns.

Fairly obviously, setting either to FALSE will turn off

that part of the operation. You can also specify a vector for

either center or scale, in which case scale()

will subtract or divide the columns by those vectors instead.

Exercise 6*: figure out how to use

apply() and scale() to scale all columns so

they have a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 1 (hint:

subtract the minimum and divide by (max-min)).

- sweep() is more general than scale; it will

operate on either rows or columns (depending on the

MARGIN argument), and it will use any operator

(typically "-", "/", etc. - arithmetic

symbols must be in quotes) rather than just subtracting

or dividing.

For example, sweep(x,1,rowSums(x),"/") will divide

the rows (1) of x by their sums.

Exercise 7: figure out how to use

a call to sweep() to do the same thing

as scale(x,center=TRUE,scale=FALSE).

So, if I want to divide each city's incidence by its mean

(allowing for adding 1) and take logs:

> logscaledat = as.data.frame(log10(scale(1 + data[, 4:10], center = FALSE,

+ scale = colMeans(1 + data[, 4:10], na.rm = TRUE))))

You can also scale the data while they are in long format,

but you have to think about it differently.

Use tapply() to compute the mean incidence in each city, ignoring NA values,

and adding 1 to all values:

> city_means <- tapply(1 + data_long$incidence, data_long$city,

+ mean, na.rm = TRUE)

Now you can use vector indexing to scale each incidence value by

the appropriate mean value - city_means[data_long$city]

does the trick. (Why?)

> scdat <- (1 + data_long$incidence)/city_means[data_long$city]

Exercise 8*: figure out how to

scale the long-format data to minima of zero and maxima of 1.

Plotting

Here are (approximately)

the commands I used to plot the scaled data.

First, I ask R to set up the graph by plotting

the first column, but without actually putting

any lines on the plot (type="n"):

> plot(density(na.omit(logscaledat[, 1])), type = "n", main = "",

+ xlab = "Log scaled incidence")

Now I do something tricky. I define a temporary

function with two arguments - the data and

a number specifying the column and line types.

This function doesn't do anything at all until

I call it with a specific data vector and number:

x and i are just place-holders.

> tmpfun = function(x, i) {

+ lines(density(na.omit(x)), lwd = 2, col = i, lty = i)

+ }

Now I use the mapply() command

(multiple apply) to

run the tmpfun() function for all

the columns in logscaledat, with

different colors and line types.

This takes advantage of the fact that

I have used as.data.frame() above

to make logscaledat back into

a data frame, so that its columns can

be treated as elements of a list:

> m = mapply(tmpfun, logscaledat, 1:7)

Finally, I'll add a legend.

> legend(-2.6, 0.65, city_names, lwd = 2, col = 1:7, lty = 1:7)

Once again, for this relatively simple case,

I can get the lattice package to do all of this

for me magically:

> densityplot(~log10(scdat), groups = data_long$city, plot.points = FALSE,

+ auto.key = TRUE, lty = 1:7)

(if plot.points=TRUE, as is the default, the plot will include all of the

actual data values plotted as points along the zero line - this is often useful

but in this case just turns into a blob).

However, it's really useful to know some of the ins and outs for times when

lattice won't do want you want - in those cases it's often easier to do

it yourself with the base package than to figure out how to get lattice

to do it.

3.4 Box-and-whisker and violin plots

By this time, box-and-whisker and violin plots will (I hope) seem easy:

Since the labels get a little crowded ( R is not really sophisticated

about dealing with axis labels - crowded labels just disappear - although

you can try the stagger.labs() command from the plotrix

package), I'll use the substr() (substring) command to abbreviate

each city's name to its first three letters.

> city_abbr = substr(city_names, 1, 3)

The boxplot() command uses a formula - the variable before the ~

is the data and the variable after it is the factor to use to split the data up.

> boxplot(log10(1 + incidence) ~ city, data = data_long, ylab = "Log(incidence+1)",

+ names = city_abbr)

Of course, I can do this with the lattice package as well. If I want

violin plots instead of boxplots, I specify panel=panel.violin.

The scales=list(abbreviate=TRUE) tells the lattice package to

make up its own abbreviations (the scale() command is a general-purpose

list of options for the subplot formats).

> bwplot(log10(1 + incidence) ~ city, data = data_long, panel = panel.violin,

+ horizontal = FALSE, scales = list(abbreviate = TRUE))

Plots in this section:

multiple-groups plot (matplot() or xyplot(...,groups),

box-and-whisker plot (boxplot() or bwplot()),

density plot (plot(density()) or lines(density()) or densityplot()),

violin plot (panel.violin())

Data manipulation:

row/colMeans(),

row/colSums(), sweep(), scale(), apply(), mapply()

4 Continuous data

First let's make sure the earthquake data are accessible:

> data(quakes)

Luckily, most of the plots I drew in this section are

fairly automatic.

To draw a scatterplot matrix, just use pairs()

(base) or splom() (lattice):

> pairs(quakes, pch = ".")

> splom(quakes, pch = ".")

(pch="." marks the data with a single-pixel

point, which is handy if you are fortunate enough

to have a really big data set).

Similarly, the conditioning plot is only available

through lattice:

> coplot(lat ~ long | depth, data = quakes)

although coplot() has many other

options for changing the number of overlapping

categories (or shingles the data are

divided into; conditioning on more than one

variable (use var1*var2 after the vertical

bar); colors, line types, etc. etc..

To draw the last figure (various lines plotted

against data, I first took a subset of the

data with longitude greater than 175:

> tmpdat = quakes[quakes$long > 175, ]

Then I generated a basic plot of depth vs. longitude:

> plot(tmpdat$long, tmpdat$depth, xlab = "Longitude", ylab = "Depth",

+ col = "darkgray", pch = ".")

R knows what to do (plot() or lines) with

a lowess() fit. In this case I used the default

smoothing parameter (f=2/3), but I could have used

a smaller value to get a wigglier line.

> lines(lowess(tmpdat$long, tmpdat$depth), lwd = 2)

R also knows what to do with smooth.spline

objects: in this case I plot two lines, one with

less smoothing (df=4):

> lines(smooth.spline(tmpdat$long, tmpdat$depth), lwd = 2, lty = 2)

> lines(smooth.spline(tmpdat$long, tmpdat$depth, df = 4), lwd = 2,

+ lty = 3)

Adding a line based on a linear regression fit is

easy - we did that in Lab 1:

> abline(lm(depth ~ long, data = tmpdat), lwd = 2, col = "gray")

Finally, I do something slightly more complicated - plot

the results of a quadratic regression. The regression itself

is easy, except that I have to specify longitude-squared

as I(long^2) so that R knows I mean to raise

longitude to the second power rather than exploring

a statistical interaction:

> quad.lm = lm(depth ~ long + I(long^2), data = tmpdat)

To calculate predicted depth values across the range of

longitudes, I have to set up a longitude vector and

then use predict() to generate predictions

at these values:

> lvec = seq(176, 188, length = 100)

> quadvals = predict(quad.lm, newdata = data.frame(long = lvec))

Now I can just use lines() to add these

values to the graph, and add a legend:

> lines(lvec, quadvals, lwd = 2, lty = 2, col = "gray")

> legend(183.2, 690, c("lowess", "spline (default)", "spline (df=4)",

+ "regression", "quad. regression"), lwd = 2, lty = c(1, 2,

+ 3, 1, 2), col = c(rep("black", 3), rep("gray", 2)))

Plots in this section:

scatterplot matrix (pairs(), splom()),

conditioning plot (coplot()),

spline (smooth.spline() and

locally weighted (lowess()) smoothing

Exercise 9*: generate

three new plots based on one of the data sets in this lab,

or on your own data.

File translated from

TEX

by

TTH,

version 3.67.

On 12 Sep 2005, 12:35.

Take the old tabular data (t1), log(1+x)-transform them,

and use as.numeric() to drop

all the information in tabular form

and convert them to a numeric

vector.

Plot them (plotting the data numeric vector

will generate a scatterplot of values on the

y-axis vs. observation number on the x-axis),

color-coded according to the

number available (rows) and point-type-coded

according the number taken (columns: note, there

is no color 0, so don't subtract 1).

order(x) is a function that gives a vector

of integers that will put x in increasing

order. For example, if I set x=c(3,1,2)

then order(z) is 2 3 1: putting

the second element first, the third element

second, and the first element last will

put the vector in increasing order.

In contrast, rank(x) just gives

the ranks

y[order(x)] sorts y by

the elements of x.

Redo the plot with

the data sorted in increasing order; make sure

the colors and point types match the data properly.

Does this way of plotting the data show anything

the bubbleplot didn't? Can you think of other ways

of plotting these data?

Take the old tabular data (t1), log(1+x)-transform them,

and use as.numeric() to drop

all the information in tabular form

and convert them to a numeric

vector.

Plot them (plotting the data numeric vector

will generate a scatterplot of values on the

y-axis vs. observation number on the x-axis),

color-coded according to the

number available (rows) and point-type-coded

according the number taken (columns: note, there

is no color 0, so don't subtract 1).

order(x) is a function that gives a vector

of integers that will put x in increasing

order. For example, if I set x=c(3,1,2)

then order(z) is 2 3 1: putting

the second element first, the third element

second, and the first element last will

put the vector in increasing order.

In contrast, rank(x) just gives

the ranks

y[order(x)] sorts y by

the elements of x.

Redo the plot with

the data sorted in increasing order; make sure

the colors and point types match the data properly.

Does this way of plotting the data show anything

the bubbleplot didn't? Can you think of other ways

of plotting these data?